Screens glow in the half-dark, Mars floating like a dusty red marble on one monitor. A countdown clock keeps running-not to liftoff, but to a faint radio ping leaving the Red Planet and inching across space toward Earth.

An engineer murmurs about “sol 418” and checks a second clock that would confuse anyone outside this room. A Martian day, measured in unfamiliar decimals, refuses to sit neatly inside any human calendar app. The numbers drift, plans flex, and sleep cycles crack.

Somewhere behind the consoles, a framed photo of Albert Einstein seems to watch it all. More than a century ago, he wrote down a deceptively simple idea: time isn’t absolute. Tonight, Mars is proving that point in a practical, workday kind of way.

Time on Mars: when your day doesn’t match your body

The first thing newcomers notice in a Mars mission control center is that the clocks don’t agree. One displays Earth time, with its familiar 24-hour cadence. Another shows Mars time, built around a “sol” that lasts 24 hours, 39 minutes, and 35 seconds.

That extra 39 minutes sounds harmless-almost like trivia. But inside the team, it reshapes everything. Wake-up calls drift later every day. Meetings creep into the night. Engineers end up eating cereal at sunset and dinner at dawn.

The day stretches just enough to keep pulling you off center. Your body wants Earth. Your mission demands Mars.

Rover wheels roll across alien rocks on a schedule that doesn’t match the people steering them. Commands sent “today” may arrive on Mars as “tomorrow” in local time. Plans become moving targets. Time-the tool we use to organize everything-refuses to stay put.

NASA’s Curiosity rover team learned this the hard way. For the first 90 days on Mars, the operations crew at JPL effectively lived on “Mars time.” Watches were set to sols. Curtains stayed drawn to block the “wrong” sunlight. Staff showed up at 3 a.m., then 5 a.m., then 7 a.m., following that slow daily slide.

On a normal calendar, nothing lined up. Monday meetings became Tuesday at 2 a.m. The week didn’t merely feel longer-it was longer, because each sol arrived 39 minutes “older” than the one before. “We were jet-lagged without moving,” one team member later joked.

On Perseverance, some leaned on sleep apps and colored lamps. Others compared it to caring for a newborn: you never really know what time it is, only that you’re exhausted. The stream of Mars data didn’t pause for yawns. The rover obeyed physics, not coffee breaks.

Einstein’s equations anticipated this in principle. Time stretches and shifts depending on motion and gravity. Mars has weaker gravity than Earth, and its days are longer. In daily life, the relativistic part of that difference is microscopic. In missions timed to the second, it becomes a stubborn constraint you can’t hand-wave away.

How space missions bend time without breaking people

Mission planners had to invent practical ways to talk about a Martian day. That’s how “sols” became more than vocabulary-they became a working unit. Sol 1 is landing. Sol 2 is the first drive. The mission timeline is stitched together not in days and weeks, but in sols, as if Mars were a client insisting on its own calendar.

Rover operations follow that rhythm. A sol begins with the rover “waking up,” checking its health, and beaming a bundle of data toward Earth. Teams on Earth receive the data later, after its slow radio journey. Overnight, humans map out the next sol’s choices: which rocks to drill, which hills to climb, which hazards to avoid.

Every command has to fit inside the limited power and daylight of that particular sol. Mars isn’t only a destination. It’s a clock that sets the rules.

The human side is messier. On Curiosity, families were given “Mars time” calendars so they could tell when their partner would actually be awake. One engineer’s spouse taped a note to the fridge: “Happy birthday (for when you’re on the right time zone).” On Perseverance, teams built color-coded schedules so everyone could see who was on Mars time and who had been shifted back to Earth time.

Space agencies gradually absorbed a tough lesson: you can’t keep people on Mars time indefinitely without paying for it. Sleep debt accumulates. Tempers shorten. Small errors start slipping into operations. Soyons honnêtes : personne ne fait vraiment ça tous les jours pendant des mois sans le payer quelque part.

So newer missions use a hybrid approach. The first critical weeks may run tightly on Mars time, then operations are eased back toward Earth time-even if that costs some efficiency. Machines can follow perfect physics. Brains can’t.

A major enabler of this balancing act is the mission software stack-systems like JPL’s Multi-Mission Ground System and planning tools used across rover projects, which help teams translate “sol thinking” into command sequences, constraints, and checklists. Meanwhile, the Deep Space Network (DSN) acts as the metronome for communication, since downlink and uplink opportunities are shaped by antenna availability as much as by Mars itself.

Independent standards bodies also quietly shape how “time discipline” works across organizations. NIST provides timekeeping references that underpin terrestrial synchronization, and international coordination through organizations like the ITU influences spectrum and communications practices that ultimately affect how reliably that Mars data arrives and how precisely it can be time-tagged.

Underneath all the scheduling chaos sits Einstein’s general relativity, adding its own subtle twist. Because Mars has about one-third of Earth’s gravity, clocks on Mars would tick slightly faster than identical clocks on Earth. The difference is tiny-nanoseconds per day-but in precision navigation and future GPS-like systems on Mars, those nanoseconds add up.

Spacecraft already live in this relativistic reality. GPS satellites around Earth require constant timing corrections for Einstein’s effects, or your phone’s maps would drift by kilometers. For interplanetary missions, the same principle applies.

Time needs calibration, like cameras and thrusters. The longer we operate around Mars, the more calibration becomes routine. Einstein’s theory stops being a chalkboard idea and becomes a line item in a project spreadsheet.

Preparing for the day humans punch in on Martian time

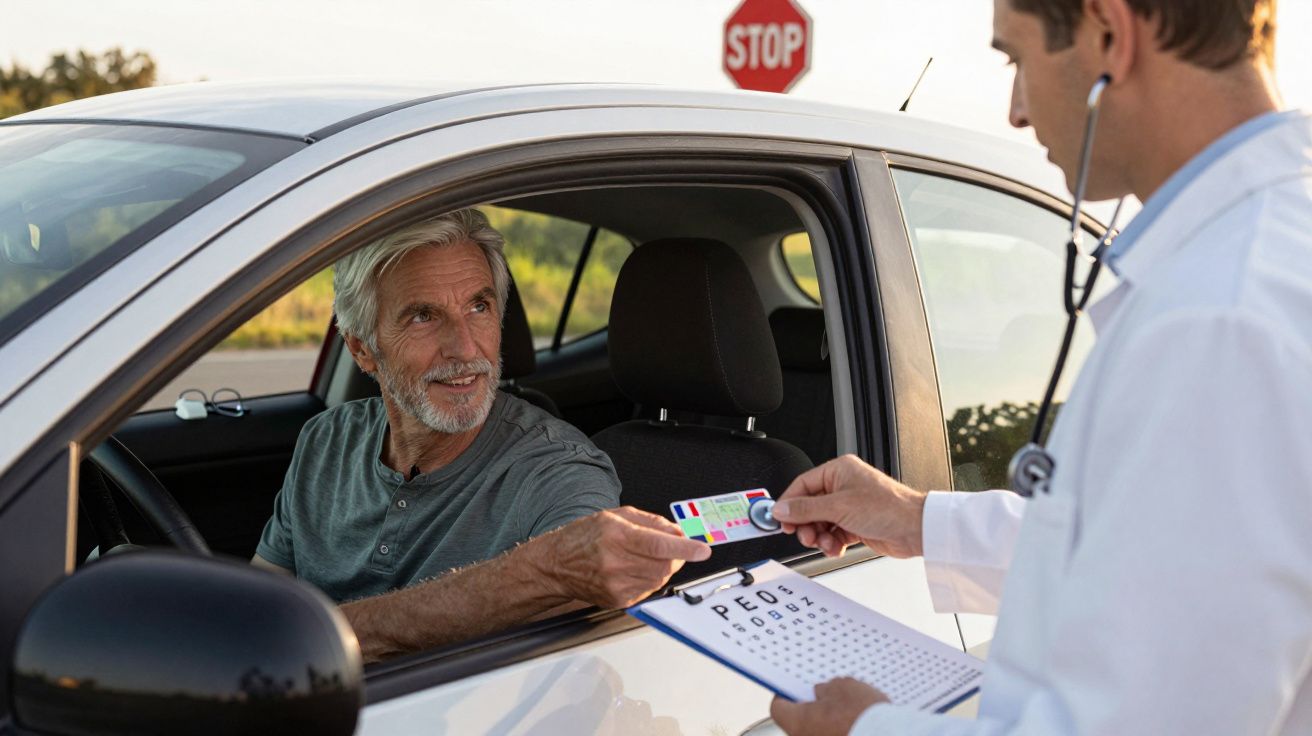

If a future astronaut steps onto Martian soil at 09:17 local time, what does that mean for their body? Space agencies are already testing that question on Earth. One approach is “Mars shift-work”: rotating crews through shifts that drift by roughly 40 minutes each day to mimic the sol.

Researchers watch what fails first-mood, performance, or sleep. They test lighting that changes color temperature to nudge the body clock along those extra 39 minutes. Apps recommend power naps at odd hours. Some early results hint that a slightly longer “day” might be less punishing than expected, as long as the shift is consistent.

The bigger challenge will be running two planets at once. Picture a Mars base where local crews live on sols, while mission support on Earth works a hybrid schedule. You may end up with “sync windows,” narrow parts of each sol where both planets overlap in reasonable working hours. That’s where the crucial decisions happen.

On a future Mars mission, some failures will be scheduling failures, not engineering ones: forgetting that a sol crossed midnight on one clock but not the other, or reading Sol 101 as Earth Day 101. Overconfidence will be tempting-“It’s only 39 minutes; we can handle it.” Many people have had that thought before a night shift that went sideways.

People in mission control talk about time the way sailors talk about weather: respect it, plan for it, and still expect surprises. Debriefs and internal reports keep circling the same coping strategies: shorter “Mars time” phases, built-in rest days, and clear rules about who lives on which clock at which moment.

One engineer put it in a line that stuck:

“Physics doesn’t care that you’re tired. That’s why the schedule has to.”

That’s where the human layer matters. Training that covers sleep hygiene, not just emergency drills. Families involved from the start, not treated as an afterthought. Shared tools that make the invisible visible.

- A dual-time watch face that always shows both Earth and Mars time.

- Shared calendars labeled in sols and days, side by side.

- Clear “off-duty” windows, protected like any other mission-critical resource.

We’ve all had the moment of looking up from a screen and realizing the day disappeared. In Mars missions, that feeling isn’t just poetic-it’s operational risk. The teams that manage it best don’t try to beat Einstein. They build routines that quietly admit he was right.

When a red planet quietly rewrites our sense of “now” - Mars time and Einstein’s relativity

Mars is teaching us that time isn’t background noise. It’s terrain to navigate, almost like gravity or radiation. As missions lengthen and crewed habitats move from slides to hardware, this “invisible” problem becomes surprisingly concrete. Who sets the alarm? Whose “morning” matters-the crew’s or the controllers’?

The answer won’t be one perfect system. It will be a culture shaped by scars, near-misses, and what each mission learns the hard way. Some future astronaut may joke that they “work flexible hours,” while quietly tracking circadian rhythm as carefully as oxygen levels. An operations lead in Pasadena might explain to their kid why Sunday breakfast is happening at what feels like Tuesday afternoon on Mars.

Einstein once wrote that the distinction between past, present, and future is a “stubbornly persistent illusion.” On the Red Planet, that illusion gets audited line by line. Every adjusted schedule, every dual-clock app, every precisely timed rover command becomes a negotiation with a universe that never promised a universal “now.”

The next time a Mars photo appears on your phone-a dusty horizon, a solitary rover track-it carries a hidden story. That image was captured on a world where the day doesn’t quite match ours, sent by machines tuned to a different tempo, and interpreted by humans who have learned to bend their lives around a planet’s heartbeat. Somewhere in that delay between event and notification, between sol and second, you can almost feel time stretching.

| Point clé | Détail | Intérêt pour le lecteur |

|---|---|---|

| La journée martienne plus longue | Un “sol” dure 24 h 39 min 35 s, ce qui décale en permanence les horaires des équipes | Comprendre pourquoi Mars perturbe autant le rythme humain et la planification des missions |

| La théorie d’Einstein appliquée | Gravité plus faible et relativité générale imposent des corrections de temps ultra-précises | Voir comment une théorie abstraite change concrètement la navigation et les communications |

| L’adaptation humaine | Passage au “Mars time”, stratégies de sommeil, calendriers en sols, limites physiologiques | Se projeter dans la vie réelle des équipes et des futurs astronautes confrontés à un temps différent |

FAQ :

- Does time really pass at a different speed on Mars? Yes, in two ways: the Martian day is physically longer than Earth’s, and general relativity predicts a tiny difference in clock rates due to Mars’s weaker gravity.

- Do NASA teams actually live on Mars time? For the first weeks of some rover missions, many teams shift to Mars time, then gradually transition back to Earth time to protect health and performance.

- Will future astronauts follow Earth time or Mars time? Most experts expect crews to live mainly on local Mars time (sols), with specific windows synchronized with Earth for critical communication.

- Is Einstein’s relativity really used in Mars missions? Yes; precise timing, navigation, and future Mars GPS systems all need relativistic corrections, just as GPS satellites do around Earth.

- Why should non-scientists care that time flows differently on Mars? Because it reveals how fragile our sense of “normal” time is, and how future space travel may reshape work, sleep, and coordination far beyond one planet.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios. ¡Sé el primero!

Dejar un comentario