In the shimmering heat of the Abu Dhabi desert, a vast energy experiment is quietly coming together-one that could redraw regional power maps.

Far from the skyscrapers and air‑conditioned malls, engineers are building what amounts to an artificial sun: a solar complex meant to deliver clean electricity continuously, without the usual gaps when night arrives or clouds drift in.

Khazna, the mega‑project that wants to beat the night

The project, called Khazna Solar PV, is rising across a 90 km² sweep of sand in the United Arab Emirates. It is being developed by Masdar, French energy group Engie, and Emirates Water and Electricity Company (EWEC). Their goal is both straightforward and audacious: supply 1.5 gigawatts of low‑carbon electricity 24 hours a day, 7 days a week starting in 2027.

Khazna aims to provide continuous, large‑scale solar power, challenging the old idea that the sun can never be a baseload energy source.

At present, no solar site of similar size consistently delivers round‑the‑clock output without leaning heavily on fossil backup. Khazna’s sponsors want to show that advanced storage paired with smart grid operation can turn a variable resource into something cities can rely on like a conventional plant.

Three million panels in the sand

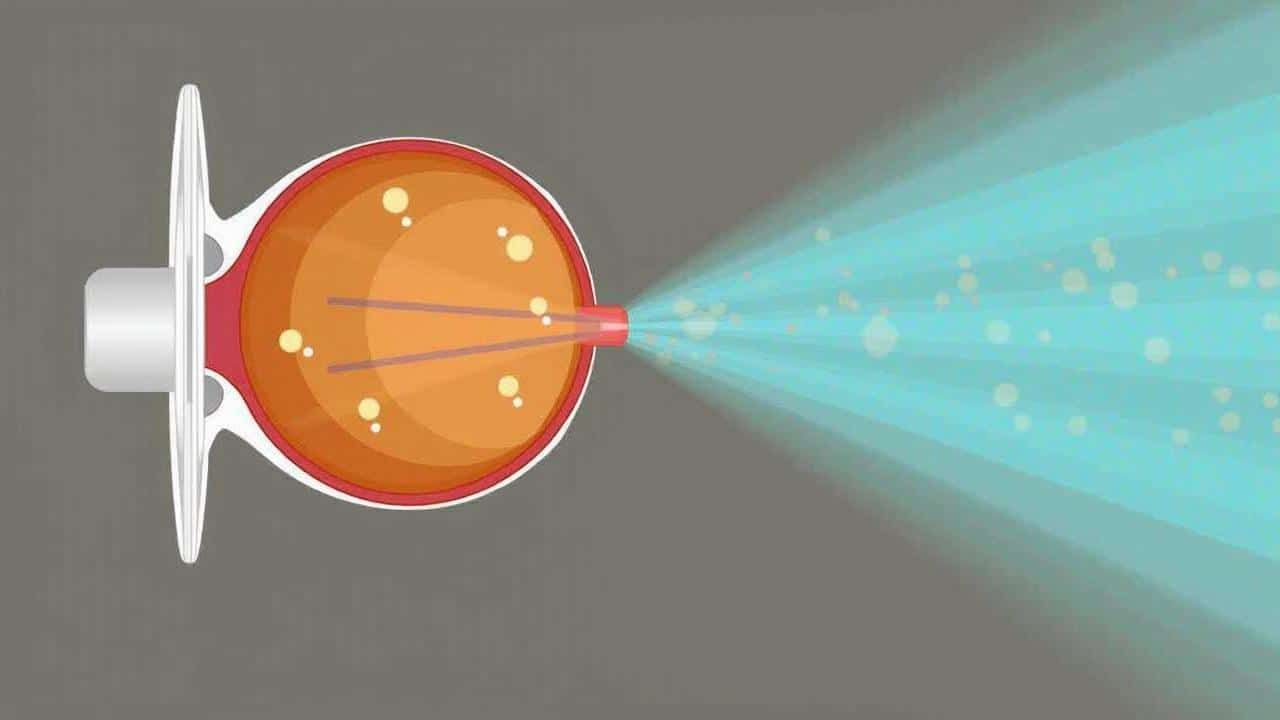

At Khazna’s core will be a solar park of roughly three million photovoltaic panels. Arranged in long geometric bands across the desert, they create a man‑made landscape that alters how the ground absorbs and reflects heat. Each panel converts sunlight into electricity, but the real challenge is how that electricity gets controlled, stored, and dispatched.

Once fully online, the plant is expected to supply power for about 160,000 homes in the Emirates, easing dependence on gas‑fired stations that still dominate much of the region’s electricity mix.

Developers also estimate Khazna could prevent more than 2.4 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions each year-roughly comparable to taking about 470,000 combustion‑engine cars off the road.

Replacing fossil power with a 1.5 GW solar‑plus‑storage hub changes both the emissions profile and the geopolitical meaning of energy in the Gulf.

How an “artificial sun” can shine after dark

The storage systems hiding behind the panels

Generating solar electricity is no longer the hardest part. The true test is keeping power available at midnight with the same reliability as at noon. Khazna will use a mix of technologies designed to smooth swings and maintain steady delivery.

- Large‑scale battery farms to store daytime power for the evening peak.

- Advanced inverters to stabilise voltage and frequency on the grid.

- Software that forecasts demand and solar production in real time.

- Potential hybridisation with other low‑carbon sources when needed.

Utility‑scale batteries-likely lithium‑ion or similar chemistries-will charge through the day and discharge at night. By sizing storage in carefully planned blocks, operators intend to maintain a constant flow of electricity even when solar output falls to zero.

Solar tracking: following the sun’s path minute by minute

All panels will be mounted on trackers that automatically adjust angle to follow the sun. Instead of staying fixed, they slowly sweep east to west during daylight, maximising captured radiation. This tracking increases total production and slightly flattens the generation curve, reducing the burden on storage.

In harsh desert conditions, these mechanical systems must withstand wind, dust, and wide temperature swings. Engineers rely on reinforced structures and sealed components to cut failures and avoid expensive downtime.

Digital brains for a desert power plant

Behind the scenes, Khazna will depend heavily on digital control. Sensors across panels, inverters, and batteries send data to central control rooms. Algorithms then process a constant stream of inputs to fine‑tune operations in real time.

| Digital tool | Main role in the plant |

|---|---|

| Forecasting software | Predicts solar output and demand hours ahead |

| Performance analytics | Detects underperforming panels and strings |

| Predictive maintenance | Identifies components at risk of failure |

| Grid management systems | Coordinates storage, production and dispatch to the grid |

These systems help keep the plant operating close to its theoretical maximum. They also shield the grid from abrupt surges or drops that can damage equipment and trigger outages.

A parallel influence comes from third‑party standards and operators that shape how such projects prove reliability. Global bodies like the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), headquartered in Abu Dhabi, help benchmark costs and performance across markets, while grid operators and market regulators increasingly require detailed reporting on availability, frequency response, and ramp rates-metrics once associated mainly with thermal plants.

Another outside player is the battery supply chain. Manufacturers and integrators-often drawing on cells and components from Asian and European industrial ecosystems-affect everything from delivery timelines to warranty terms. In practice, the long‑term success of 24/7 solar hinges not only on engineering choices in the desert but also on procurement discipline and the durability guarantees offered by suppliers.

A symbol of the Gulf’s energy transition

The Emirates built economic strength on oil and gas, yet they are now investing heavily in renewables. Khazna joins other large solar installations in the region and sends a clear signal: the Gulf does not intend to remain locked into the fossil era.

For Abu Dhabi, projects like this reinforce energy security while freeing more hydrocarbons for export instead of domestic power generation. For foreign partners such as Engie, they provide both commercial opportunity and a proving ground for clean technologies that can be scaled globally.

Desert sunshine, once seen as a burden, is turning into a strategic asset as climate constraints and market pressures tighten.

Challenges hidden behind the promise

Dust, heat and the cost of reliability

Building an artificial sun in the desert brings its own constraints. Dust storms cut the light reaching panels and force frequent cleaning campaigns. With water scarce, operators test dry cleaning robots and low‑water methods to keep performance from slipping.

Extreme heat can reduce panel efficiency and shorten the life of batteries and electronics. Cooling approaches, improved coatings, and ruggedised design become core elements of the business model-not optional technical add‑ons.

There is also the question of cost. Massive storage systems and high‑performing panels remain expensive, even as prices continue to fall. To compete with gas generation, developers typically need long‑term contracts, low financing costs, and highly efficient operations.

Land use and ecological footprint

A 90 km² solar park reshapes the local environment. Vegetation patterns, wildlife corridors, and soil conditions all shift when millions of panels cover the ground. Even if deserts look empty, they support ecosystems adapted to extreme conditions in delicate balance.

Designers must account for habitat disruption, glare risks for birds, and micro‑climate changes at ground level. Research from other desert solar farms has shown shifts in soil temperature and moisture, which can ripple through insects, reptiles, and small mammals.

What Khazna Solar PV means for future “artificial suns”

If Khazna delivers what it promises, similar solar‑plus‑storage complexes could appear in other sun‑rich regions-North Africa, the American Southwest, parts of India, and Australia. Each location would adapt the model to local conditions, but the central principle would remain: convert intermittent sunshine into a dependable backbone for the grid.

Some researchers already model national power systems where solar, wind, storage, and flexible demand meet most electricity needs. Projects like Khazna provide real operating data for those simulations, reducing uncertainty around costs, reliability, and bottlenecks.

For cities, the shift raises practical planning questions. Industrial zones may cluster near renewable hubs to secure clean power contracts. Data centres could connect directly to desert solar parks and batteries. Households might see tariffs that reward consumption when the “artificial sun” is strongest and storage reserves are full.

The concept also introduces new risks and benefits for energy planning. Concentrating large capacity in one mega‑site creates a potential single point of failure that cyberattacks, technical faults, or extreme weather could exploit. At the same time, big integrated plants can manage storage and forecasting more efficiently than a scattered patchwork of small installations.

In the Abu Dhabi desert, three million panels and vast battery banks will soon test these trade‑offs. The project will not look like a star in the sky, but for the cities tied to its cables, this artificial sun could quietly redefine what reliable power means in a warming world.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios. ¡Sé el primero!

Dejar un comentario