The bus had barely pulled away from the station when your stomach started that slow, disloyal flip. Your gaze stayed pinned to your phone, trying to squeeze in one last reply, but your body had different priorities. The road bent, the screen jittered, and suddenly the air seemed too warm and too thick. Sweat prickled along your forehead. A familiar wave climbed from your gut to your throat, as if the ground had quietly tipped beneath your seat.

You lifted your head, swallowing hard, performing “fine” for anyone watching. Outside the window, the scenery glided by like nothing was wrong. Inside your skull, it felt like disorder.

Why does your own body turn against you at the worst possible moment?

When your eyes and inner ear quietly start an argument

Sit in the back of a car and stare at your phone for five minutes. You can almost sense the beginning: a slight unease, a swirl behind the eyes, a thin nausea with no obvious cause. The driver chats, music plays, but your attention collapses into that small storm building in your head.

Your eyes report, “We’re still, we’re just reading.”

Your inner ear murmurs, “No, we’re moving. A lot.”

That disagreement is the whole issue.

Think back to the last time you tried reading on a winding mountain road. On the page, the letters don’t move. Outside, the world snaps past in quick, jagged fragments. The car slows, accelerates, leans into curves. Your inner ear - a tiny, fluid-filled labyrinth - registers every tilt and every surge.

By the third or fourth tight bend, your stomach joins the debate. Your skin goes pale, palms dampen. You crack a window, hungry for cold air, half sure you’ll need to beg the driver to pull over. It feels arbitrary, unfair, almost targeted.

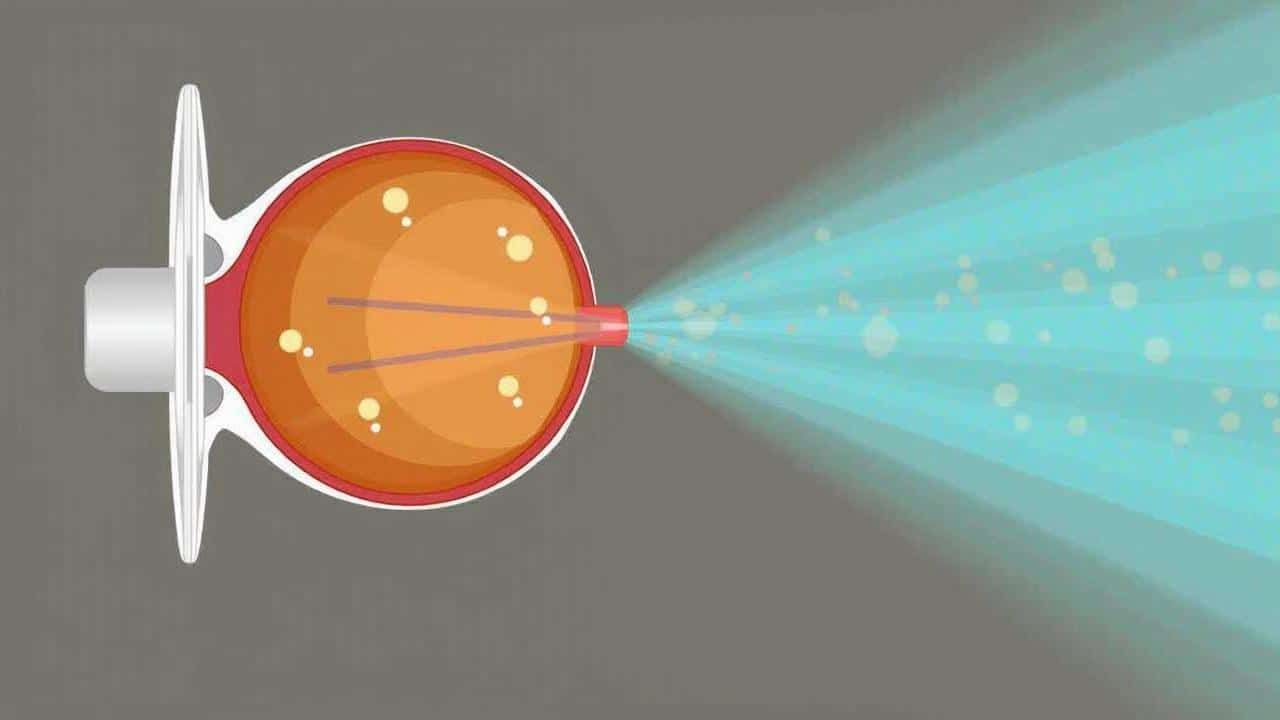

Behind this private drama, the biology is surprisingly straightforward. Motion sickness is essentially your brain caught between two systems issuing conflicting reports. The vestibular system in your inner ear tracks motion and balance. Your eyes deliver their own detailed update. When they don’t align - you feel motion but don’t see it, or see motion but don’t feel it - your brain treats it like an emergency.

Some researchers even suggest your brain reads this mismatch like poisoning, setting off nausea as an ancient protective response. Sensory conflict turns into physical revolt.

How to calm the “sensory war” before it ruins your trip

The most effective tactic is almost painfully simple: give your brain one coherent story. Help your eyes and inner ear agree. In a car, sit in the front and look far down the road rather than at your phone or your lap. On a bus or train, pick a seat facing forward and anchor your gaze on a steady point near the horizon.

When your eyes can see what your inner ear already feels, the confusion eases. The brain settles down. Often, your stomach does too.

A lot of people unknowingly set themselves up to suffer. They choose the worst places: the back seat, a sideways seat, a rear-facing seat. Then they drop into a book, a tablet, or messages they “must” answer. Ten minutes later, they’re shocked they feel terrible. You’re not fragile or defective - you’re just creating ideal conditions for the mismatch to flare.

It also helps to recognize the role of the environment, not just the vehicle. Strong fumes, heavy meals, and stuffy air can lower your tolerance fast. Even mild anxiety can amplify nausea once the sensations begin, turning a small wobble into a full-body alarm.

If you want extra support beyond seat choice and gaze, it’s worth knowing there are established third-party options. Some travelers rely on OTC antihistamines such as dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) or meclizine (Bonine), while others use prescription scopolamine patches for longer trips. For non-drug approaches, organizations like the CDC’s travel health guidance often recommend practical steps-fresh air, stable gaze, and avoiding reading-while some people find ginger products or acupressure bands (like Sea-Bands) helpful for mild symptoms.

Let’s be honest: almost nobody plans perfectly every day. We don’t map our lives around the inner ear. We just climb in, sit wherever, and hope for the best. That’s why the same scene keeps replaying.

Sometimes the kindest thing you can do for yourself on a trip is to accept that your body has rules of its own, and travel with them instead of against them.

- Pick your seat

Front of the car, near the middle of a boat, over the wings on a plane: these tend to be the steadiest spots for your inner ear. - Give your eyes a job

Look outside toward the horizon or a distant fixed point, not at fast-moving close objects. - Use your breath

Slow inhales through the nose and longer exhales can reduce the panic that intensifies nausea. - Play with posture

Keep your head as stable as possible, supported by a headrest if you can. Quick head turns feed the conflict. - Know your triggers

Heat, hunger, strong smells, and poor sleep all lower your threshold. One small factor can push you over the edge.

Living with a body that sometimes disagrees with the ride (motion sickness)

Motion sickness has a way of making you feel childish, even a little embarrassed. Other people scroll through TikTok in the back seat like nothing is happening, while you’re gripping the armrest and counting down minutes. But this isn’t a failure of willpower. It’s simply your sensory wiring turned up a bit.

Once you understand the real conflict is between your eyes and your inner ear, the story shifts. You’re not “being dramatic”; you’re stuck in an alarm system that’s doing its job a little too aggressively. And you can collaborate with it. Experiment with different seats, different times of day, small snacks before travel, fresh air, wristbands, and medication if you truly need it.

The same journey can feel completely different once your brain stops fighting itself.

You might still dread that curvy road or that choppy boat ride. But you’ll know what’s happening - and that small piece of understanding can dull the fear and, slowly, hand you back a bit of freedom.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory conflict | Mismatch between what the eyes see and what the inner ear feels | Helps you understand why nausea suddenly appears |

| Seat and gaze choice | Front seats, horizon focus, minimal head movement | Gives concrete ways to reduce or prevent motion sickness |

| Personal triggers | Heat, screens, smells, fatigue, reading while moving | Lets you adapt your habits and plan trips with less discomfort |

FAQ:

- Why do I only get sick when I read or look at my phone in the car? Because your eyes say “I’m still, I’m just reading,” while your inner ear clearly feels the car moving. That conflict confuses your brain and can trigger nausea.

- Why do some people never get motion sick? People vary in how sensitive their vestibular system is and how their brain handles conflicting signals. Some brains tolerate the mismatch without sounding the alarm.

- Is motion sickness dangerous? For most people it’s miserable but not dangerous. The real risk is dehydration from vomiting or, in rare cases, not being able to function in transport when you need to.

- Do those wristbands and pills really work? Acupressure bands help some people, especially for mild symptoms. Medication like antihistamines can be very effective, but they may cause drowsiness and should be used thoughtfully.

- Can I “train” my body to stop getting motion sick? Many people improve over time with gradual exposure and good habits: better seat choice, horizon focus, controlled breathing. Some sensitivity remains, but the threshold for feeling sick can rise.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios. ¡Sé el primero!

Dejar un comentario